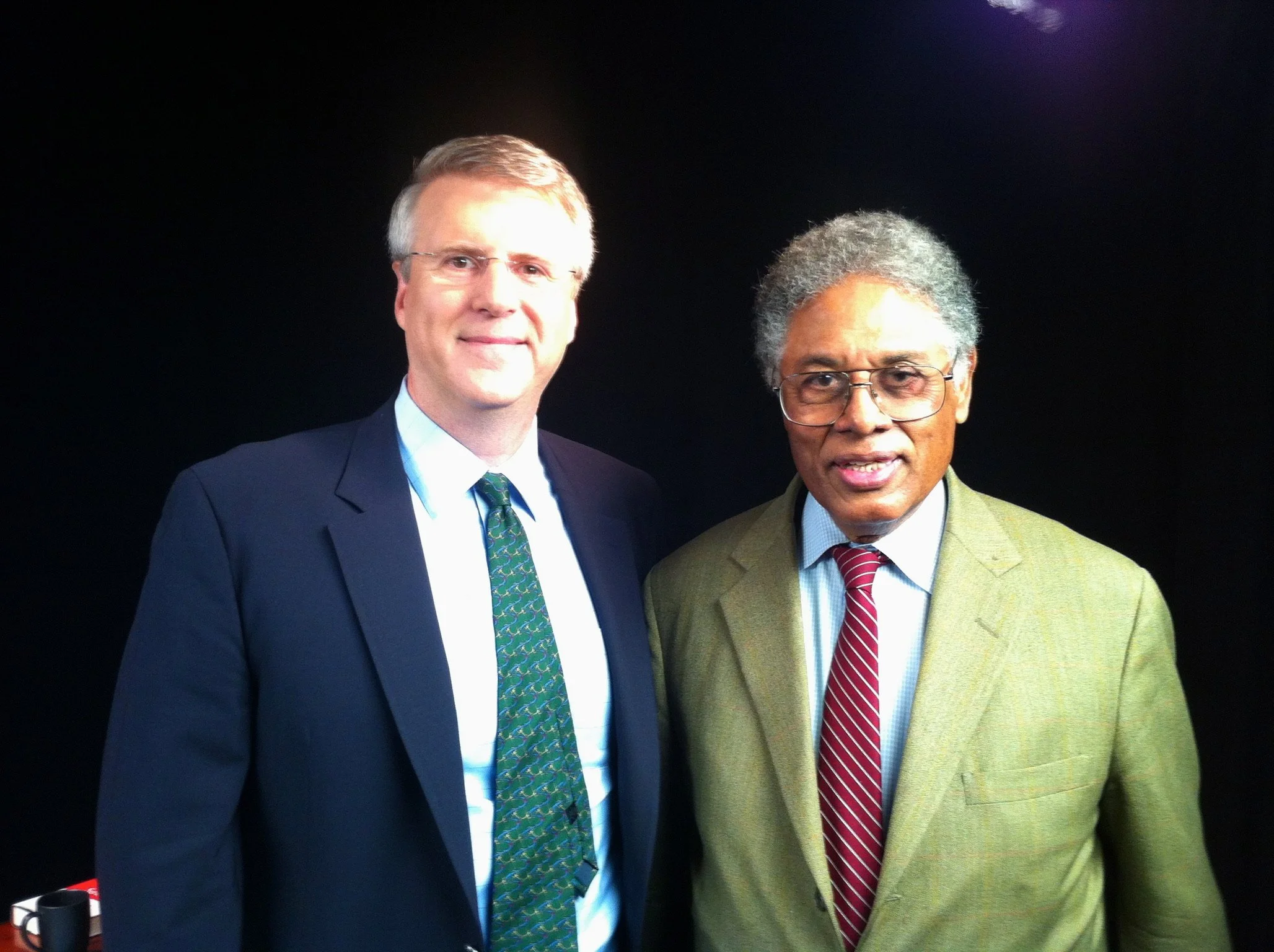

Interview with Peter Robinson

Peter Robinson is the Murdoch Distinguished Policy Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is the host of Uncommon Knowledge and a former presidential speechwriter.

Impressions and Impressions

Contents

Max Raskin: I want to start with the fact that you’re a good impressionist, which I think is interesting for a presidential speechwriter. If you want to impress someone, who is your go-to impression?

Peter Robinson: First of all, I make sure that the audience is filled with boomers and up. People who have a knack for impressions pick them up when they’re kids, so I can do Ronald Reagan, John Wayne, and Jimmy Stewart. What I mean to say is every person I do is dead, Max.

I think if I were 30 years younger, I could have picked up Barack Obama. James Rosen does the best Barack Obama I've ever heard.

MR: Could you do Trump?

PR: No. There's a very famous brain scientist called Mike Gazzaniga. Great guy. My wife and I were deciding whether to raise our children bilingually — my wife is Cuban — and Mike said there's a magical decade from the age of two to the age of 12 when children can learn anything you throw at them, including how to speak a language unaccented. But after the age of 12, something mysterious that we still don't understand just shuts down. And I am pretty well convinced that if you don't pick up an impression by the age of 12, you'll just never quite get it.

Now, obviously that can't be quite true because there are the Dana Carveys of the world whose jobs are to remain current, but it's certainly true in my case.

MR: Are you a Saturday Night Live fan?

PR: I'm a fan of the bits of Saturday Night Live that pop up in my X feed because my feed is filled with like-minded people. Saturday Night Live is very uneven. The older you get, the choosier you get about the ways you spend your time.

MR: Do you have any people on X who you think are must-follows?

PR: Yes — Damian Thompson writes for the London Spectator. If you're Catholic — you're not — but if you are Catholic and paying close attention, by now you're sick of all this hagiography of Pope Francis. Damian Thompson's much sharper about realities on the ground in Rome. And so I like him because I care about that stuff and he's actually reporting with an edge.

Charlie Cooke is just so much his own man. He's in the business of commentary, but he doesn't truckle to his audience or to Trump or to any variety of the zeitgeist you'd care to name. He always writes beautifully.

MR: What’s “truckle”?

PR: “Truckle” — to bend or to shade your opinions to curry favor or to remain in favor. Charlie doesn't care about anybody's favor. I love that.

MR: When you see something you like do you share it with your friends or are you a content consumer?

PR: Max, Max, you know me well enough to know that I'm a taker. Are you kidding me? What I observed about myself is that if I put up a post, 10 minutes later, I go back to see if it's been liked. Another 10 minutes later, I go back to see again…it eats up my whole day. Aside for posts related to my show for Hoover, Uncommon Knowledge, I tend to limit myself through a ferocious act of discipline just to reposting the odd item.

My friend John Podhoretz does this all the time: He gets in fights. I don't have time for that. I don't have the discipline. I don't have the rhino-like hide that John seems to have. If somebody gets angry with me, it upsets me for three or four hours afterwards.

MR: Podhoretz reminds me what Murray Rothbard said about his inspiration for writing, he said, "Hatred is my muse."

But I guess my question was more personal — when you see something funny is your instinct to share it with friends?

PR: Oh, that goes right into the family feed. My wife and all five kids have a thread that's alive all day long.

MR: Is that fun for you?

PR: Oh, definitely that's fun. The kids put up pictures of where they are at that moment. We're always exchanging ideas on movies or novels or television series.

I'm a little embarrassed to admit this, but my wife and I have a poodle and my daughter and her husband have a poodle, and we’re always taking pictures of them. So all day long, we're taking pictures of poodles and sharing them back and forth. But, Max, keep that quiet.

Skiing with Bill Buckley

MR: So you knew a lot of the old guard?

PR: I knew Bill Buckley really quite well.

MR: I heard you went skiing with him.

PR: Over and over and over again. I spent two months in the winter of 1987 to 1988 as Bill's research assistant. I'd been in the White House for years by then, and I'd never taken a vacation, so I had weeks and weeks of vacation time coming to me. And I went with Bill and stayed with him in Gstaad for his annual stay in Switzerland. I was his research assistant on a book about his show Firing Line.

For the first three weeks, Bill and I were alone together because his wife, Pat, was in New York dealing with their apartment which had flooded. And I realize now that Bill was trying me out for two or three days, and then he decided I was all right. The result was that Bill put the word out to all the hostesses in Gstaad that anytime they invited him to an event, I was to be invited along with him. I ended up at lunch over and over again with — speaking of old guard — James Clavell, the author of Shogun. There was a dinner of just six or seven of us, and two of the people were the former king and queen of Greece. I actually got to know Roger Moore pretty well.

MR: The actor?

PR: The actor.

MR: What did you do there?

PR: The pattern was we would start work at seven. We would work until about noon, break for lunch, and then go ski for a couple of hours and then come back and get another piece of work in before breaking for dinner. So that pattern obtained for almost two entire months. And when we were working, we were at desks facing each other, so I got to know Bill really quite well.

MR: Was the skiing intense?

PR: Oh, it was all groomed. Bill was old enough to have stiffened up in the joints a little bit, but I'm chuckling to myself because I realized that he was younger then than I am now. He was a very good skier for his age, and he was also quite a fearless skier.

Was there elegance or grace? No, I think we would have to say not. There was speed and there was an agility, and there was also just sheer enjoyment. One day I was skiing a bit behind him and he came to a stop and just looked uphill waiting for me, and I swished in next to him and he said, "Peter, I've been skiing in Gstaad since I was a boy. Memorize this moment. These are the most perfect conditions I've ever seen." And then he turned and skied on down the hill.

MR: Would you drink when you worked? There's something about alcohol and the old guard.

PR: The morning session was totally dry. I was staying at a hotel or motel across the street from the Chateau de Rougemont, which was the big place Bill rented each year. I'd have breakfast and turn up and we'd sit down. I would get there about 7:00, and Bill was already hard at work by then, and that was silent, hard work. He would take occasional phone calls, but he was writing his column, and he was working on turning one of his novels into a play. And on top of that he was taking comments from me — written notes on passages that he might compose for the book on Firing Line. It was typical Bill. He was working on three or four things at once. After the morning session would come lunch, then skiing, and then when we would return for an afternoon session of more work. Before dinner Bill would have a Kir and a cigar. And whereas the mornings were silent, in the late afternoons he would put on jazz.

MR: What kind of jazz?

PR: Ella Fitzgerald. I remember Ella Fitzgerald.

MR: Do you remember what kind of cigars he smoked?

PR: They were short, horrifying, little black stubby things. He offered, and I never inhaled a cigar in my life, but even just taking it into my mouth, it was just too strong for me.

He had terrible emphysema in this final year or two, so it all became really kind of horrible. Later in life he wrote a column about smoking saying that, libertarian though he had been all his life, if he could push a button and make smoking enforcibly illegal in an instant, he would do just that.

Vices

MR: Do you have any vices? Do you drink? Do you smoke?

PR: I often pause to give thanks for the vices to which I've never been tempted.

Gambling doesn't particularly interest me, except every four years I'll put money on presidential candidates. Not huge amounts, but I'll put money on presidential candidates.

MR: How good is your record?

PR: Oh, I always win. Are you kidding me?

MR: Have you ever lost?

PR: No, because I'm such a chicken and cheap bettor. If I'm not sure, I don't put money down.

For the primaries, I think I may have lost money. In 2016 when Trump was one of 17 primary candidates in the GOP race, he was my 17th choice. I just could not picture — and I wasn't alone here — I just could not picture that he could possibly win the nomination. And so I think I lost a little money betting on Ted Cruz on that one. As I recall I very timorously put a little bit of money on Trump against Hillary. And by a little bit, I mean a very little bit. I may have bet the grand total of 25 bucks or something like that.

MR: This doesn’t seem like such a vice. Do you drink?

PR: Only with friends. My real vices are procrastination and overeating. Not grossly overeating, but enough to wish I were 10 pounds lighter and to have wished that for a couple of decades now.

Reagan, Friedman, Buckley

MR: For someone who has never listened to any of your interviews before, what would be the interview that you would point them to that you're either most proud of or is most representative of your work?

PR: So my answer is that there was one moment when my interview guest was Milton Friedman. We were talking about the federal budget surplus, and I stopped him to say he was making a moral argument, not an economic one. And Milton Friedman looked at me for a moment and said, “Fundamentally doesn’t it all come down to a moral argument?”

He was such a brilliant, technically gifted economist, but he was also a deeply humane figure. And for him, economics was not a game. Economics was not building intellectual models. It was doing what was right. You had a responsibility to use your head to reason through what you could do to best help your fellow citizens. I just found him so impressive in every regard.

MR: I’ve seen that interview, but I think that’s the wrong answer. I think the correct answer is the interview you did with Justice Scalia back in maybe 2012. That was so good. I think that's what turned me on to your interviews. I thought that was just so good.

PR: Thank you.

So before I got to know Justice Scalia, I got to know a couple of his kids. Gene Scalia and I were really pretty good friends. I had no idea that Gene Scalia's father was a lawyer, let alone a judge. This was before he got named to the Supreme Court. The point I'm trying to make is that I think maybe the reason Milton Friedman made such an impression on me is that I was never in anything other than awe of Milton Friedman. I should have been in awe of Justice Scalia from the beginning to the end, but because I'm a deficient human being, I thought of him as Gene's dad.

MR: Did you know Reagan on a personal level?

PR: Max, you know the answer to that. Nobody knew Ronald Reagan on a personal level. So really all you can do is sort of count the hours you spent in his presence, and it wouldn't have been that many. The speechwriters had occasional meetings with him, but only occasional — unlike the relationships that speechwriters had with Richard Nixon before Reagan or George W. Bush after him. Nixon and W. would call their speechwriters into the Oval Office and kick around ideas with them. Nixon would try out paragraphs by reading them aloud and seeing what Safire thought or what Buchanan thought. Ronald Reagan was so accomplished as a writer and giver of speeches and had such a defined sense of what he wanted to say and of his own voice. W. came to the White House still in some ways unformed as a voice or as a figure, and so they were not only trying to figure out what he should say, but what he should sound like in saying it. There's none of that in Reagan. By the time he got to the White House, Ronald Reagan was already Ronald Reagan.

Reagan was also a very self-contained person. He came up as an actor in the old days when the writers’ bungalows were over there and the soundstage was over here. You didn't kick around ideas with the writers. There were runners who brought the scripts over. So the real action between Reagan and his text took place when he was alone upstairs in the White House editing. I never, ever wrote a speech for him, not one, that he didn't mark up in at least some way, proving to me that he'd read every word of it himself. Some of them he marked up more than others. So that's where the real action took place.

But we got to know him, first, because it was our job to try to inhabit the mind of Ronald Reagan, and second, because we all loved him.

By the way, that's significant. There's something called the Judson Welliver Society, which is a club for former presidential speechwriters. In the old days, the two tables of writers who always understood each other — even though our politics were opposite — were the Kennedy writers and the Reagan writers. Ted Sorensen and I became pretty good friends because we understood each other, I felt. John Kennedy was the biggest thing that had ever happened to Ted Sorensen, and Ronald Reagan was the biggest thing that had ever happened to me.

The Nixon writers…well, that was much more complicated. They respected Nixon, but they didn’t love him. Working for Nixon had been a very rough experience for all of them. The Johnson writers — that was complicated too. But the Kennedy writers and the Reagan writers, we both just loved our presidents.

Reagan was wonderfully gregarious, totally lovable, and seemed to promise friendship, but there was always a distance in the end. He was always self-contained in the end.

MR: You must have told the story of how you wrote the “tear down this wall” line for Reagan a million times. I’m not going to ask you to tell it again, but what’s your best time telling it? Is there a video I can share?

PR: The most concise version is on the website of the National Archives.

MR: Of the people you've met in your life, who stands out to you as world-historic?

PR: I got to know Bill Buckley very well. Actually, that's one case where I really came to love him, but never quite stopped being in awe of Bill. But I always felt that I was extremely fortunate because I got to know all three of my heroes.

MR: Who are the three?

PR: Bill Buckley makes conservatism accessible. He explains it, he makes it cool. Milton Friedman establishes the intellectual foundation. And then Ronald Reagan is the one who puts it into practice in electoral politics. And without each of those three, in my opinion, the revival that took place in the 1980s would've been impossible. So I consider all three of those men just gigantic figures.

Tech Bros

MR: Who do you want to meet today in this new conservative world?

PR: I have a very high regard for the people who are holding it together. This isn't the kind of interview where you want to go through what we like about Trump, what we dislike. I have a very high regard for much of what he's doing, not all, but I think there's just no doubt that he's personally chaotic, that this is not an easy chief executive to work for.

I have a very high regard for the people who seem to me to be doing a very conscientious, extremely difficult job of holding things together. Keeping our institutions functioning and intact. Scott Bessent, Marco Rubio and Speaker Mike Johnson — all strike me as tough, shrewd, courageous and remarkably selfless.

MR: What about any of the people who are not politicians but just thinkers on the right?

PR: On the intellectual side, the tech bros fascinate me.

Peter Thiel. Peter is always thinking deep into the future. He has one of the most completely original minds I’ve ever encountered. He’s constantly looking at matters in ways no one else has even considered.

Marc Andreessen is brilliant and patriotic and articulate, and you have in him an old-fashioned Midwestern American. He's worth untold billions of dollars now, and when you go over to his house in Atherton, he's got security and walls, but in his head, Marc Andreessen is still a kid from a small farm town in Wisconsin and it comes through and it is so appealing, so commendable. He really, truly thinks of himself as an ordinary guy from the middle of the country.

Another person whom I find more and more impressive the more I watch him is Brian Armstrong of Coinbase — he's very understated and he's quite modest. The first time I met him, Charlie Munger had just died, and so I said to Brian, "All I know about crypto is what I read in Charlie Munger's obituaries, and Charlie Munger said in effect, when crypto can be used for transactions, send him a postcard. Why was Charlie Munger wrong?" And Brian Armstrong replied, "Well, I'm not sure he was wrong." And then he proceeded, "Here's what we have to find out. Here's something else we need to find out…"

In all of Silicon Valley, he's the only person who would've begun an answer to my question with a touch of self-doubt, a touch of, "This is empirically verifiable and it's going to work the way I think it's going to work, or it may work the way Charlie Munger thought it would work"—that kind of openness to reality. And yet his ambitions are staggering, staggering — he wants to reinvent the entire banking system of the planet.

Right around here, right in Silicon Valley, these guys are thinking totally unfettered thoughts.

MR: You're a godfather to these tech bros.

PR: Are you calling me old? Max, I'm slapping you. I'm reaching through the screen and slapping you.

America Still Works

MR: I don’t think people recognize that this generation of influential billionaires and tech titans all look up to you. A lot of people will say you’re instrumental in their ascent. I find a lot of people your age and of your worldview get stuck in their ways of thinking. How do you stay excited about things?

PR: I've seen this attributed to Napoleon, but I can't find the citation so if Napoleon didn't say it, he should have. "If you want to understand a man, you must know what was happening in the world when he was 21." When I was young, I was in the Reagan White House, and I took that stamp in a way that I will never take the stamp of anything else again in my life. When you're young, there’s one moment of total freshness and openness and almost susceptibility.

I work at the Hoover Institution. What's distinctive about the Hoover Institution? First of all, intellectual giants. Tom Sowell is with us and still totally present. Second, it's in the middle of Stanford University. I'm surrounded by kids. I get older, they never do. And this stream of kids has included Peter Thiel and David Sacks. I've only gotten to know Marc Andreessen recently. He didn't go to Stanford, but I've known his wife, Laura, for years because she was an undergraduate right here at Stanford. The gratitude I feel for this cannot be expressed.

And then I have this show where it's my job to sit across from people and ask them questions. I’m constantly learning. Not that I’m any sort of intellect. It’s just that I have to keep up in order to do my darned job.

I keep thinking about this in the context of China. There are always going to be more Chinese than Americans. They now have an economy that's big enough to permit them to spend whatever they want to on defense. Our only sustainable advantage against them is going to be innovation. Who's smart, who's building new companies in the defense space? What could be more fascinating? Really, really smart and accomplished entrepreneurs and engineers — and the stakes are nothing less than western civilization.

This is the thing that I find the most exciting and the most invigorating. I'm not sure I'll say it very well, but I think you being you, you'll get it. It's proof that America still works. The conditions have changed so completely — it’s no longer the Cold War, which was the overriding issue when I was going through college in my 20s and very earliest 30s. Totally new circumstances now. And yet, you've got Marc Andreessen, Peter Thiel, David Sacks, Brian Armstrong, Elon Musk, every one of these people and others. They're brilliant. They've mastered an entirely new technology. They're designing a new kind of economy, and yet fundamentally they are still patriots. They love this country. They want our democracy to work.

Reagan had this beautiful line that we're only one generation away from losing our freedom. We're also only one generation from ceasing to love the country. And yet the United States of America seems to renew itself again and again and again.

MR: You’re waxing pretty poetic now. I hope you don’t have to go soon.

PR: It's your job in editing to make sure I wane a little bit.

The Church and Ayn Rand

MR: So you’re a regular mass-going Catholic?

PR: That's true. I'm a sinner, but I try to get there maybe three, four times a week in addition to Sunday

MR: A man more sinned against than sinning.

PR: Oh, no, no, no. I do plenty of sinning.

The reason I have no excuse not to go to mass is because it's six minutes away by bicycle. I go right here on the Stanford campus.

MR: Do you bike?

PR: Yes.

MR: Is that how you stay in shape?

PR: I go out in the carport here at home every so often and throw a few weights around.

I really have reached a stage where it's not so much that I'm giving up running in favor of walking, it's that when I go for a run, I move so slowly that it has become indistinguishable from walking.

MR: Do you listen to music when you run?

PR: Music or podcasts and if I go for a long walk, I'll make a phone call or two. I love talking to friends while I'm walking.

MR: Can I do a quick three-minute rapid fire question-and-answer?

PR: Do what you need to do.

MR: Jazz, classical, or rock. Pick one.

PR: Not rock. Classical or jazz — if you said, "You have to choose one or the other or we'll shoot you," I'd say shoot me. I can't imagine living without good jazz, and if you told me you were going to deny me Beethoven and Bach or listening to something by Mendelssohn I hadn't heard, I'd say shoot me. I couldn't give up either one of those.

MR: What's the last television show you binge-watched?

PR: I'm binge-watching it right now — Ludwig.

MR: What is the movie you think you've seen the most in your life?

PR: The Wizard of Oz.

MR: Do you floss?

PR: I do, but keep that quiet because I've been working on my friend Jay Bhattacharya — now that he's director of NIH, he gives away $50 billion a year. I said to him, "Jay, all I want is a grant for three million to see what happens if I start flossing." I'm thinking there must be a way he can tuck that into the budget somehow.

I floss because it's the only thing I'm sure that I can do well.

MR: You're going to resist answering this question, but I just want you to answer it: Are you more like your mom or your dad?

PR: I'm probably more like my father, but that is not as I would wish it.

My father was a very good man, but he was a worrier, and he was given to moods. I fight against both of those tendencies myself.

MR: Has your religiosity waxed and waned over your life?

PR: You're observant, so you'll get this. I’ve always been sort of religious. I tried atheism when I was in college, but I could only keep it up for about two weeks. The existence of God has always struck me as just obvious. Eventually I converted to Catholicism—I was 27 years old. John Paul II was Pope.

MR: How did you grow up?

PR: It was just kind of non-denominational Protestant. My parents would go to a church based on whether they liked the minister.

MR: In upstate New York?

PR: I grew up in Vestal, which is a town just outside Binghamton.

I say Binghamton, as if that's decisive, because if you don't know where Binghamton is, I can't help you. It wasn't close to anything else.

MR: I know from Binghamton.

PR: You do?

MR: Did I hear that Tony Dolan was part of your religious conversion?

PR: If I had met Tony any sooner, I would've become Jewish!

I'm joking about Tony as if he were still alive. It will sound so callous. I don't mean that at all.

I didn't get to know Tony well until after I converted. Probably the major figure in my conversion would've been my own reading, but there was also Bill Buckley, and then there was a wonderful priest I went to see in Washington to iron out my last objections. He's now dead, but he was brilliant and hilarious, a man called Lorenzo Albacete, Monsignor Lorenzo Albacete. He was a Puerto Rican who trained in nuclear science and then felt a vocation to the priesthood quite late in his life.

MR: Despite all this intellectualism it just always stands out to me how concerned you are about people. You said a phrase that has always stuck in my head talking about Atlas Shrugged — that from any page you can hear a voice “To a gas chamber — go.” I remember exactly where I was in DC when you said it to me.

PR: That’s a quotation. That's not me. Whittaker Chambers wrote a very famous review of one Ayn Rand novel or another. Because he saw in her that Nietzschean worship of strength, which implies disregard for those who are weak or seen as weak.

If I have any empathy for other people — you may be giving me too much credit, but if I do — it’s because I’m just a regular chump doing the best he can. The other morning, I got in a good workout on the rowing machine. Afterwards I was positively glowing with general contentment. Then I got in the shower, and the hot water handle fell off. The plumber couldn’t get there for three days and you don’t even want to know how much he charged when he did. That’s the way life is for most of us, I figure. God is good but there’s always something.